Consider the future for our current kindergarten students and what the world will be like when they graduate in the year 2031. Given the technological advances we are witnessing today, any description of our near future that does not resemble something out of a science fiction story may likely represent an underestimation of the changes that will impact our lives. It is within this context of accelerating change that we are tasked with the challenge to reimagine school and learning. If one word could be used to describe the current educational landscape, it would indeed be change. Three factors associated with driving this change are arguably the areas of social and emotional development, personalised learning, and emerging technologies.

Social and Emotional Development

While the discussion surrounding social and emotional skills is not new, there is an ever-increasing importance placed on this area. The developmental abilities of empathy, initiative, curiosity, resilience, and adaptability will be vital in preparing our students for the rapid changes in society we are experiencing. How do schools ensure that students are ready to communicate effectively, engage with others in meaningful and authentic ways, and embrace the inherent beauty of human nature?

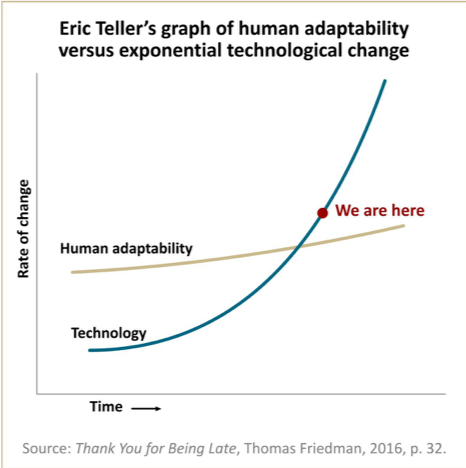

Thomas Friedman argues in his book, Thank You for Being Late, that our students are growing up in an age of acceleration in which technological change is outpacing human adaptability, as per Eric Teller’s graph.

If it is correct to assume that technology and globalisation will not slow down, then our focus must be on improving human adaptability by ensuring a population that is more agile, creative, and adaptable.

Schools also have a responsibility to reconsider what is now commonly viewed as our outdated and misaligned systems and metrics of success, which are associated with rising rates of mental illness. The narratives related to achievement and personal realisation are considered to be contributing to the adverse health outcomes found in society. How can schools and society support our students in redefining measures of success that include balance, health, and well-being? Several collaborative groups are seeking to answer this very question, which is exemplified by the Mastery Transcript Consortium and the work of universities and K-12 schools to redefine student transcripts.

Personalised Learning

In the recent KnowledgeWorks, The Future of Learning Report, the authors describe the future of learning as one where, “flexible configurations of human educators and mentors, along with digital learning coaches and companions, will be coordinated seamlessly to support learners’ short- and long- term needs and help all students reach their goals.” Personal growth of this nature is requiring the development of customised learning relationships and connections with an expanding range of learning partners. Our current school structures do not necessarily always lend themselves well to this system of learning, particularly when considering an expanded view of what constitutes mentors and learning coaches.

Schools are experimenting with systematic changes, such as flexible scheduling, blended learning opportunities involving both face-to-face and online opportunities, the redesign of campus learning spaces, and alternative credentialing, including a complete redefinition of report cards and transcripts. Technology is, of course, also challenging schools in many ways as learning continues to be more and more personalised due, in part, to a push towards 1:1 computing environments and an increase in adaptive software systems.

Emerging Technologies

Many of us have already experienced adaptive learning in which a program analyses our performance in real time and then modifies the teaching methods and curriculum focus. The use of an adaptive program or app to learn a new language is now commonplace. The field of education will undoubtedly continue to be revolutionised as machine learning becomes more prevalent. As computer systems use data and statistical techniques to “learn” on their own and continue to improve performance without a human explicitly programming the computer, schools will need to continue to adapt to this new reality. Teachers can increasingly use learning and predictive analytics to connect millions of data points to arrive at conclusions and predict future performance based on past data. One of the key outcomes we see today is an increase in personalised opportunities and students guiding and pacing their learning.

What we are experiencing now is considered to be the third educational revolution, following the high school movement and education for life in the early 1900s and then the support for higher education at around the midpoint of the last century. As the Future of Learning report highlights, schools are now becoming more fluid in that we are moving from a fixed structure driven by administrative convenience to one that is a fluid network of relationship-based formats that reflect a learners’ needs, interests, and goals. Algorithms and artificial intelligence are providing personalised learning opportunities and educators who best match each learner’s needs. We are also increasingly seeing a demand for flexible and customised learning environments which many of our current administrative structures act as constraints.

While there is much work ahead of us, the International School of Zug and Luzern’s (ISZL) foundations of an adaptive and evolutionary mindset provide our community with an effective basis to embrace the changes in the educational landscape we are experiencing today and will continue to do so in the future. Learning at ISZL is guided by an inquiry-based and transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary program that values play, experiential and project-based learning, and hands-on experiences, which are supported by a relationship-based and connected community. It is these set of values, philosophical approaches, and sense of community that will both empower and enable ISZL to adapt and thrive in an environment that requires critical building blocks for a digital economy while not allowing technology to outpace our humanity.

Reference:

KnowledgeWorks. 2018. Navigating the Future of Learning Forecast 5.0. Retrieved from https://knowledgeworks.org/resources/forecast-5/